Seriously, where is everybody?

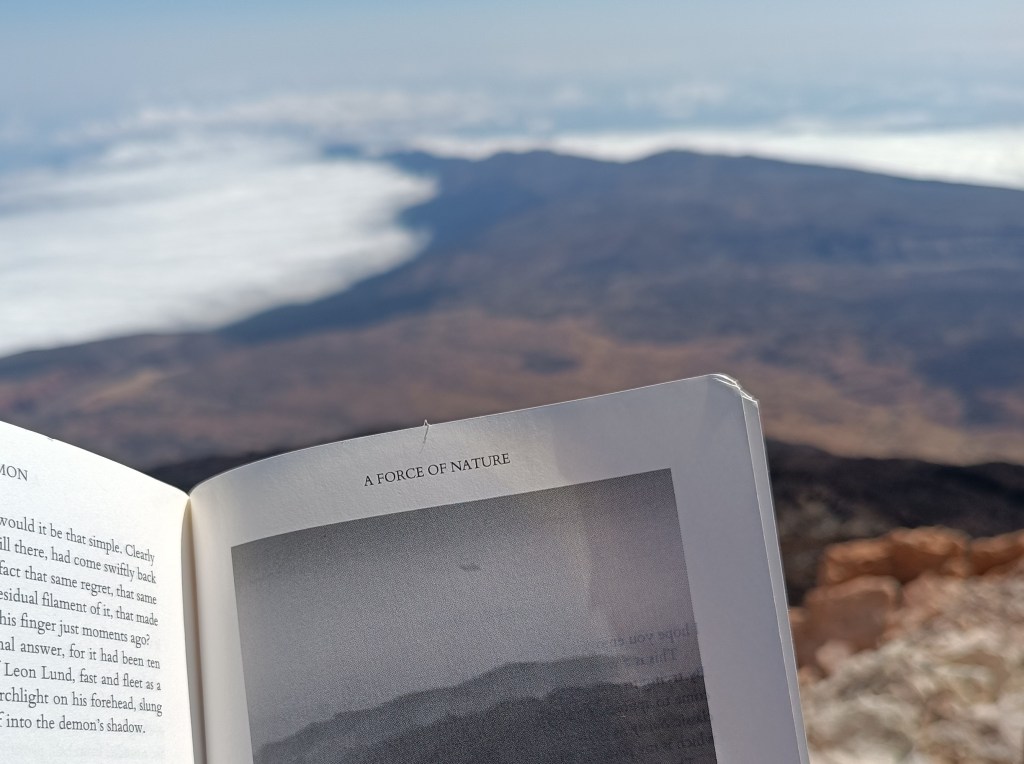

If you visit El Pajar on a Thursday, you might feel as though you’re entering a ghost town. As you stroll along the main promenade, book in hand, your sole companions would be the tree leaves rustling softly in the breeze. Only your Gran Canaria guide had told you that El Pajar was a lively, boisterous place…

What mysterious force could have wrought such a poignant void of humanity?

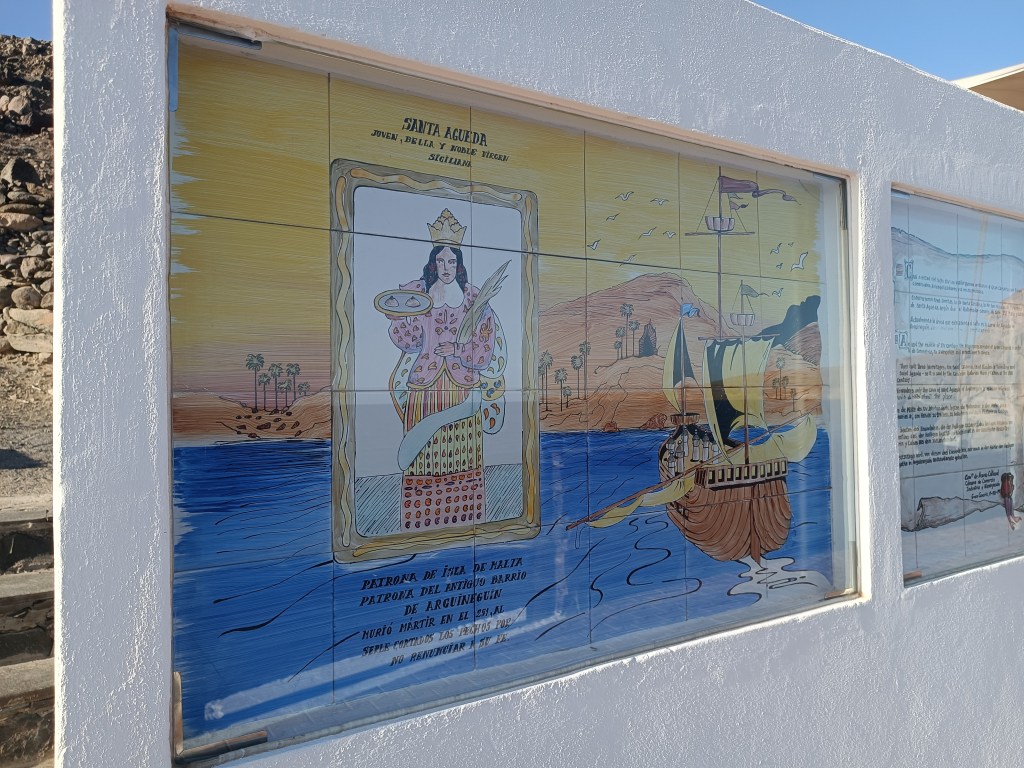

Assuming the mystery has a divine origin, you decide to traverse the town and visit the local shrine (Ermita) carved into the nearby cliff. From there, you gain a panoramic view of Santa Águeda Bay, encompassing the beach, the town, and the adjoining cement plant. If you squint, you might even discern the Maspalomas lighthouse across the bay.

The bay gets its name from the holy figure living inside the small cave-shrine behind you. That’s where the soul of El Pajar resides. Saint Águeda was a Christian martyr, and her story is summarized in the mural nearby. While her martyrdom is described only in Spanish, the artistic depiction makes it self-explanatory.

The shrine is closed for the day. Nonetheless, you approach the gate, hoping to catch a glimpse of the Saint, perhaps even ask her why there’s nobody around. To your astonishment, she’s just awakened from her power nap and kindly answers your question:

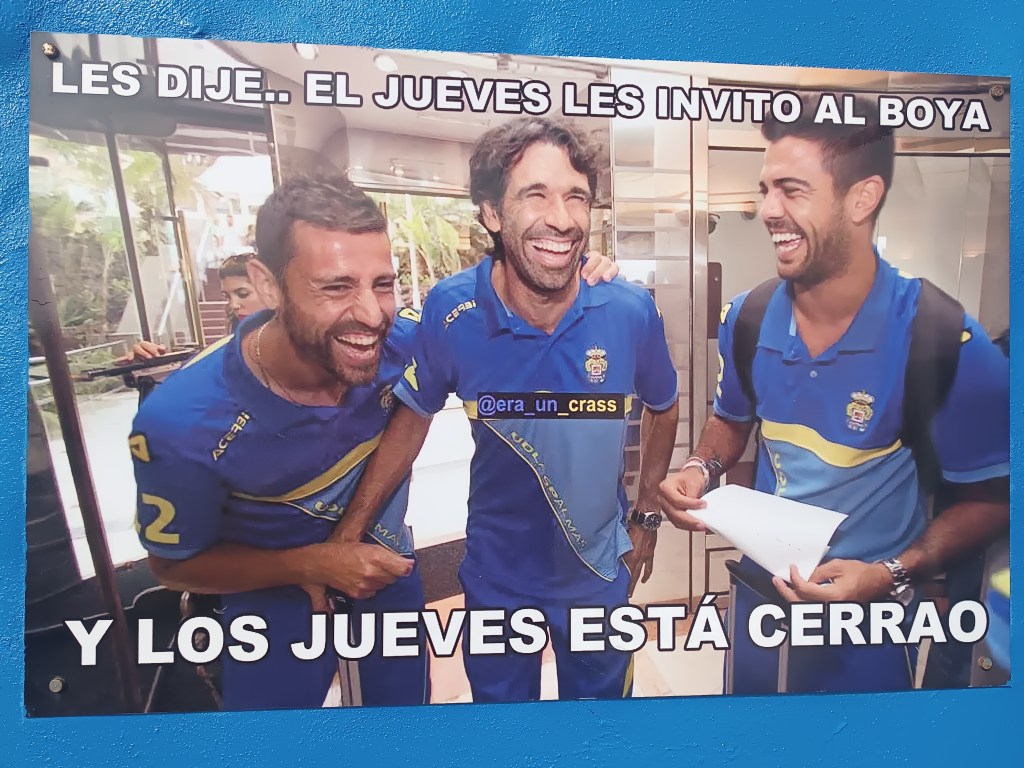

“¡Es que el Boya está cerrado!”

El Boya. Yes, that beach restaurant you saw on your way in. That’s the beating heart of El Pajar, and on Thursdays, El Boya is famously closed. Life outdoors just isn’t the same without it, so the locals tend to stay indoors.

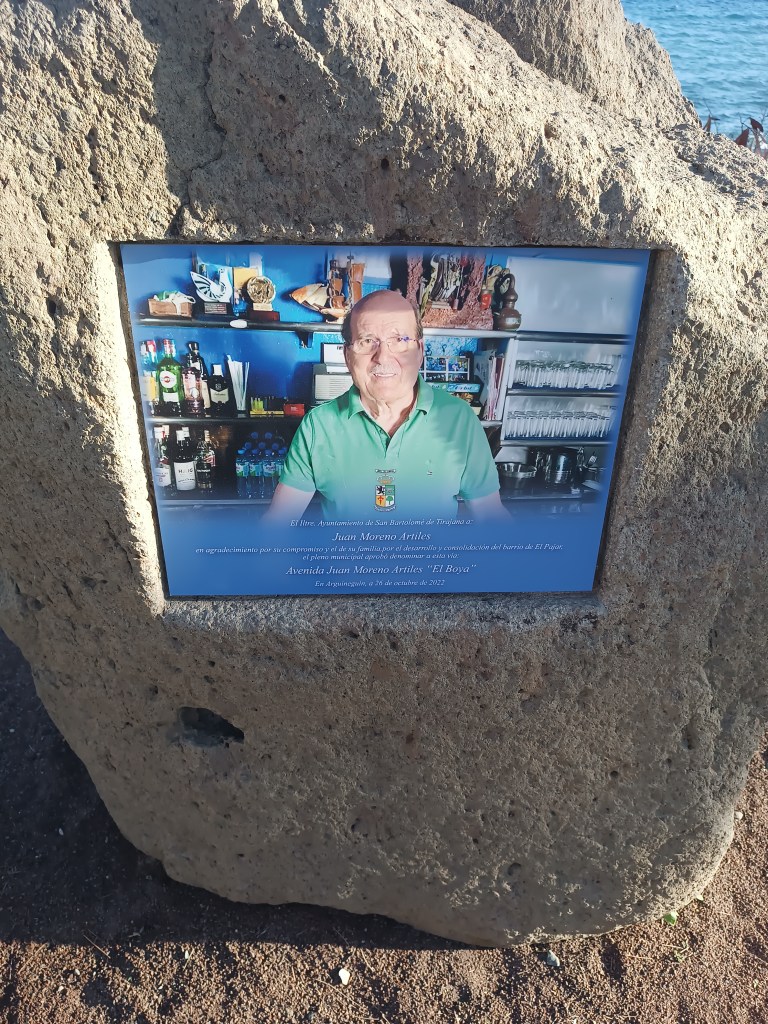

Returning to the promenade, you gaze at the boarded-up restaurant and read about its history and significance on the many placards scattered around the area. Apparently, it started as a small eatery for local fishermen in the 1950s. Now, the main promenade in El Pajar is named after the bar’s owner.

If you visit on any other day, you’ll have the chance to try their delicious, and deliciously cheap, homemade food (their specialty being the Octopus Ropa Vieja). You can peruse the menu on their website below and even listen to the restaurant’s exceedingly charming ‘theme song.’ It will bring a smile to your face, even if you can’t understand the lyrics.

The history and development of El Pajar as a town are inseparable from that of the beach restaurant, and both are deeply intertwined with the cement factory. The cement business serves as the lifeblood of El Pajar, fueling much of its economic growth since the 1950s. This reality explains one of the biggest artistic licenses in the novel. That massive eyesore of a plant isn’t there against the locals’ wishes, nor do they rally against its presence. Despite the inconveniences of having such an ungainly neighbour, the locals have grown accustomed to seeing it every day —many for their entire lives. While it may be a stretch to say they love the plant, they would likely feel a profound absence if it were to disappear.

As a foreigner, you struggled at first to wrap your head around that. But after your quiet little visit, you understand it better. El Pajar is a lively town with boisterous blood, a thriving heart, and tons of soul. Take one of those away, and maybe only the town’s ghost would be left behind.

***

P.S. El Boya does not have “morena frita” (that was another artistic license) but you can have it on “La Marinera”, the famous fish and seafood restaurant on La Puntilla, in the north end of Las Canteras.