Of all the statues and sculptures featured in The Fire Demon novel, Manuel Bethencourt’s Atis Tirma monument in the Hotel Santa Catalina Gardens stands out as my favourite. I find the sheer feistiness and foreboding of its subjects truly captivating. And the crowning touch—the aboriginal figure vaulting off in defiance, pointedly away from the colonial-style hotel in the background—delivers a powerful statement of resistance and unyielding freedom.

Still, if you’re the kind of tourist who reads TFD, you’ll probably want to know more. Who were these people? What are their names?

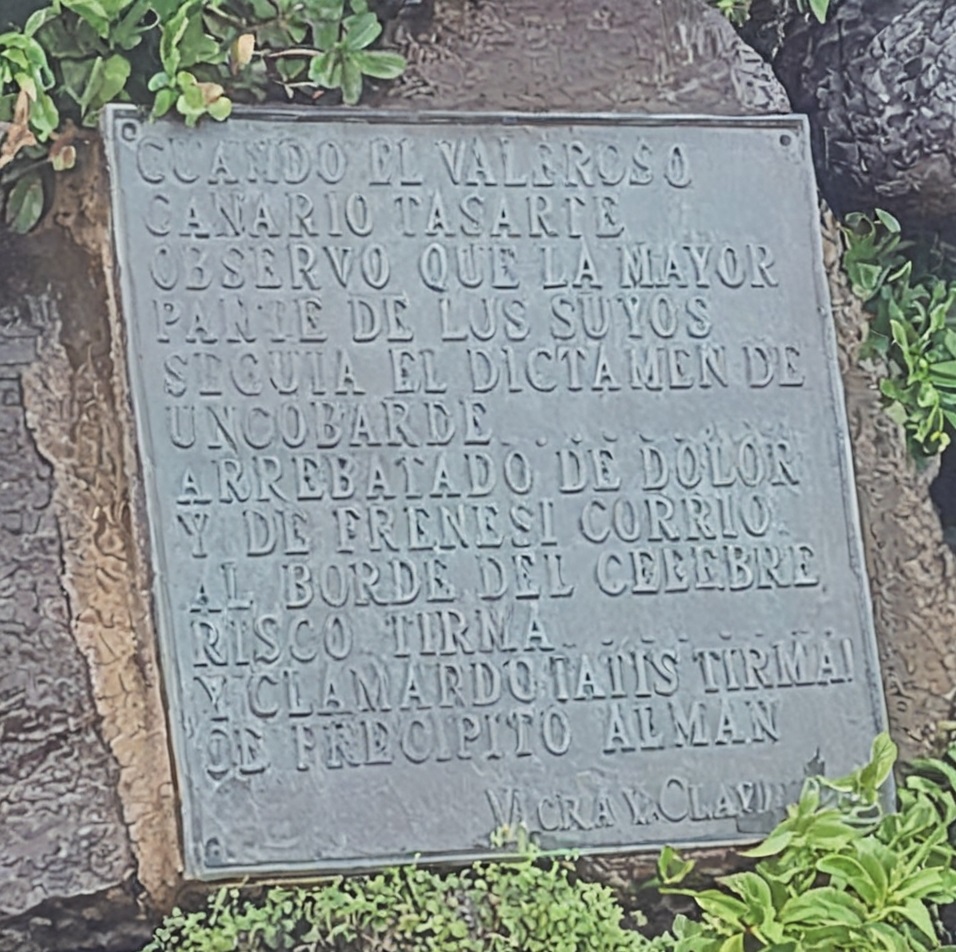

Okay, let’s start by reading the inscription at the base, just behind the lowest figure.

“And when the brave Tasarte saw that most of his fellow Canarii heeded the coward’s call, gripped by pain he ran to the edge of the Tirma cliff, and, to the cry of ‘Atis Tirma!’, he jumped off.”

This is a stylized account of the tragic culmination of the Spanish Conquest of Gran Canaria in 1483. The conquest marked the end of a gruelling five-year campaign by the Spanish Army to subdue the native Canarii, the indigenous people of Gran Canaria. Genetically linked to the Berber tribes of North Africa, the Canarii, and more broadly, the Guanche people, are believed to have arrived on the archipelago thousands of years earlier. How they managed this remains a mystery, as no archaeological evidence of maritime capabilities has been found.

By the time of the Spanish conquest, the Canarii had established a structured social hierarchy, with the names of many rulers and tribal leaders etched into the historical record. Among them were the warriors Doramas—after whom the nearby park is named—and Tasarte, as well as King Tenesor Semidan, Princesses Guayarmina and Arminda, and the King’s ward, Bentejui.

After the Spaniards captured King Tenesor, the young Bentejui rallied the princesses and led a fierce resistance in the highlands, marked by several bloody battles, until the last of the Canarii took refuge in the Ansite fortress (near present-day Santa Lucía). In a surprising turn, King Tenesor then reappeared at Ansite, now bearing the Spanish name Fernando Guanarteme, and attempted to persuade Bentejui to end the struggle. Bentejui refused, but the Canarii eventually surrendered. Feeling betrayed, Bentejui followed the path of the warrior Tasarte, who had taken his own life after an earlier battle, and ran to the Tirma cliff, where, to the cry of ‘Atis Tirma!’ (For this land!), he jumped off.

The exact location of the Tirma cliff is unknown, but it is certainly not the Roque Nublo (that’s just another artistic license on my part). If you visit the archaeological museum at the Ansite fortress, you’ll see the area is not lacking in potential cliffs, so let’s say it’s one of those and call it a day.

As for the two young princesses, Guayarmina and Arminda, they were reluctantly handed over to the Spaniards as part of the surrender agreement. This pivotal moment was immortalized by the painter Manuel González Méndez in his work Rendición de Gran Canaria, which hangs today in the Canarian Parliament.

And that female note brings us back to the Atis Tirma monument. 99% of the pictures you will see of this monument online feature the three male figures in the front. I have no problem naming them—from top to bottom—Bentejui, Tasarte, and Doramas. However, there’s actually a woman’s figure at the back, and she’s the feistiest of them all, chasing the invaders away with a rock in her hand.

Who is she? What’s her name?

You should already know. If not, here’s a hint: she has no love for Farhad Nilsson. Not one bit.