To the surprise of absolutely no one who’s read TFD, I am—unabashedly, incurably—a James Bond fan. A member of the global congregation that can argue passionately about whether Dalton was ahead of his time (he was) or whether Craig peaked too early (he did). So, if you’re a Bond fan reading this, consider this blog post a raised glass across the bar. We’ve all been through it together.

For context—and because no two Bond fans agree on anything—here are my “parameters”:

- First Bond film in cinemas: The World Is Not Enough.

- Favourite film: Casino Royale (2006).

- Least favourite: Spectre.

- Favourite actors: Dalton and Craig.

- Favourite movie villain: Goldfinger.

- Favourite novel: Live and Let Die.

And yes, since we’re being honest, I also loathed the end of Craig’s run. Spectre and No Time To Die delivered two of the weakest villains in the franchise’s history—a cardinal sin in Bondworld—and neither film stuck the emotional landing they were so desperate to attempt. But the future looks brighter: new leadership, a clean slate, and Denis Villeneuve reportedly stepping into the director’s chair.

So, as we stand at the threshold of Bond 26, here is my wish list—five ways 007 movies can rise again.

1) Cast a Younger, More Boyish Bond (No, That Doesn’t Mean Reinventing Him Beyond Recognition)

Let’s get this out of the way early: we don’t need Bond to be gay, Black, a woman, or re-engineered into some identity-politics mascot to “modernise” the franchise. We simply need something new—and that something is vulnerability to another man. The kind that isn’t melodramatic or sentimental, but structural. Built into the character. A Bond who enters the world not fully formed, but a Bond who has something to learn, someone to fear, someone to grow under.

This is precisely what Craig, for all his strengths, could never project. Not through lack of acting prowess (he’s superb) but because of pure physical presence. He’s the blunt instrument type. From the first post-credits scene in Casino Royale, he’s already bossing another agent around like a schoolmaster. Even when he was meant to be a rookie, he moved like the biggest apex predator in the room. His vulnerability played beautifully with Judi Dench’s M—maternal, moral—and with most of his leading ladies but not with any man. Not with Mallory (a disastrously flat on-screen chemistry), not with fellow operatives, and barely with allies like Mathis or Leiter, who had to be seconds from dying for Bond to show a crack of emotional exposure.

So please—no more “blunt instrument” arcs. We’ve already seen that.

Bond 26 has the rare opportunity to chart an origin story without shouting the word “origin.” Cast an actor who reads younger and slighter—someone who can be mentored, intimidated, moulded. Think of the tension that could arise from Bond respecting, admiring, or even quietly fearing a male mentor who is smarter, stronger, or more seasoned.

My pick? Josh O’Connor, by a mile. The perfect combination of boyishness and bite—a face that can blush, tremble, and kill. That’s the kind of fresh dynamic the series has been missing.

2) Give Us a Proper Villain Plot (Real Stakes, Real Countries, Real Consequences)

If Bond 26 wants to get its swagger back, it needs one thing above all: a villain with a grand, complex, slow-burn plot that captures the imagination. You know—the kind of plot that doesn’t just “happen” in the background but unfolds, tightening around Bond (and the audience) until the final act snaps shut. It’s stunning how rare that’s become. Remember when discovering a villain’s plan was half the thrill? When clues dripped in piece by piece until the last reel blew the doors off? It’s been ages.

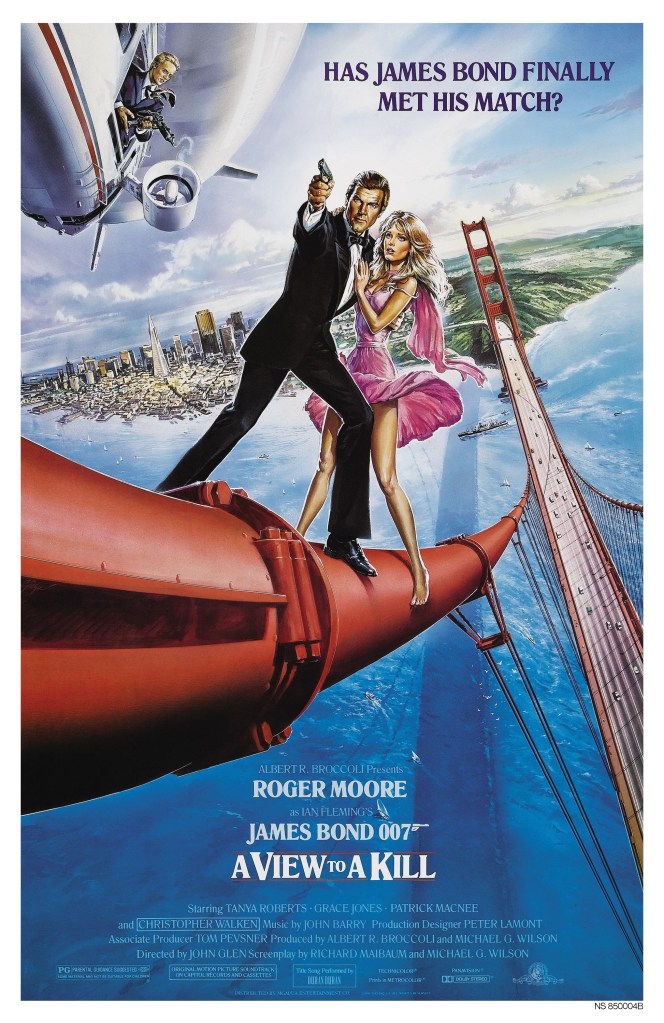

Look at the recent movie posters: Craig glowering alone, perhaps with a leading lady, maybe with a gun if marketing is feeling nostalgic. Compare that to the classic posters—the era when the villain was a marquee character. Bloefeld, Scaramanga, Zorin—faces, silhouettes, colour palettes built around them. You saw a Bond poster and instantly knew who Bond was up against. It told you the flavour of the film. Nowadays? The villain is an afterthought, almost an inconvenience.

And the truth is: Craig’s era was starved of meaningful villain plots. The plots were so muted and politically sanitized they barely existed. We’ve been living in a PG world of “shadowy organisations” with no countries, no victims, no stakes you can actually visualize. All smoke and no fire.

- Spectre? Tell me the plot. Tell me the villain’s plan. Tell me anything other than “flowers for brother James.”

- No Time To Die? What even was Safin doing? Germs? Nanobots? A garden?

- Skyfall gave us Silva with a personal vendetta—executed wonderfully, but still small-scale.

- Quantum of Solace had an actual geopolitical plot, but it was so grounded it bordered on municipal. Water rights? You can find more sinister water villains in the UK utilities sector.

- Casino Royale? The plot is good, but vague: “funding terrorism,” “winning back money,” meh.

Which means—and I cannot believe I’m typing this—the last proper, bonkers, fully-fledged villain plot was in Die Another Day.

Yes, the ice palace fever dream.

Yes, the DNA-swapping North Korea cosplay.

But at least there was something to uncover. Something escalating. Something with imagination.

Say what you want about the Brosnan era: every film had a proper villain scheme. Some hit the bullseye (GoldenEye), some fired into the curtains (Tomorrow Never Dies), but all were fun, ambitious, and defined their films.

And then there’s the villain as a character—where modern Bond has drifted even further. The gold standard is still Fleming’s writing, particularly Live and Let Die:

“No one looked up from his work. No one would slacken when Mr Big was out of sight. No one would put a jewel or a coin in his mouth.

Baron Samedi was left in charge.

Only his Zombie had gone from the cave.”

That’s a Bond villain. A big macher. Someone whose very presence commands dread. Someone Bond must respect before he defeats them.

Give us a villain who gets a proper Iago moment—the second-act triumph, the moment where the hero stumbles, the table turns, and the audience gulps. When was the last time we saw a villain thoroughly school Bond? Le Chiffre cleaned Bond up too early, then choked on a bullet before he could win anything meaningful. Silva’s plan worked only until it didn’t. Safin? Please.

Honestly, the last respectable second-act villain victory was Elektra King in The World Is Not Enough—and even that didn’t land as it should have.

Bond 26 must restore the ancient recipe:

- A villain with a world-shaking plan

- Real nations, real stakes, real victims

- A mastermind who dominates Act Two

- A threat big enough to force Bond to grow

That’s what these films used to be about. That’s what makes Bond Bond.

3) Respect the Henchmen (Especially the Smart Ones)

A great Bond villain is never great alone. To carry out a grand, nefarious plot, they need competent, capable, devoted henchmen. Not just muscle, but specialists: strategists, assassins, loyal operatives who maintain the audience’s suspension of disbelief. When done right, these characters create tension, escalate stakes, and give Bond someone dangerous to clash with between encounters with the Big Bad.

Physical henchmen can provide levity if their extremity borders on the outrageous—think Jaws switching sides or Oddjob’s stoic absurdity. But for intellectual henchmen, the rule must be absolute: do not use them as comic relief. Nothing deflates a villain faster than the suggestion that a clown is running part of their operation. If the mastermind’s success hinges on someone incompetent, the audience stops respecting both of them.

This is why No Time To Die faltered so badly with Waldo Obruchev. How can we invest in a plot when its central architect is treated as a punchline? He invented the most terrifying bioweapon in the franchise’s history, yet no character—hero or villain—shows him the slightest respect. He’s mocked, kicked around, and dispatched with a one-liner. It makes the plot feel weightless. If Obruchev is disposable, then so is the threat he created.

A Bond story is built on networks of capable adversaries and allies. For the audience to buy the grand design, the characters must buy it too. Respect the smart henchmen. Respect the intelligence behind the threat. That’s how you sell the stakes—especially when they’re outrageous.

4) Commit to Location

One of the great pleasures of Fleming’s novels—especially in the 1950s—was their travelogue quality. You didn’t just follow Bond on a mission; you travelled with him. Jamaica, Harlem, Istanbul, Kyoto, Miami—these places weren’t just settings. They were characters. They shaped the plot, the villains, the allies, even Bond’s own inner landscape. The early films understood that. Think of You Only Live Twice taking you into the sumo arena or The Living Daylights teaming Bond with the Mujahideen—moments that root the story in a place and time, for better or worse. Yes, some of it has aged poorly, but at least the films committed to the culture and atmosphere of the locations.

Paradoxically, the globe-trotting Craig era is the least “travelogue” period in Bond history. The films hop from city to city, but the locations are interchangeable, flavourless, reduced to postcard backdrops. Every main character—ally or enemy—feels like they’ve been ubered in from somewhere else. No one belongs anywhere, which means nowhere matters.

And No Time To Die is the worst offender.

Don’t be hypnotised by Matera’s warm lanterns and stone stairways. That opening could have taken place in literally any picturesque town in southern Europe with minor rewrites. Matera never shapes the story. Norway becomes a pretty bridge. Cuba is reduced to a generic salsa bar. Jamaica too. Nothing in the plot requires these places; nothing about the locals influences the action. Even Paloma, supposedly Cuban, feels like she’s been flown in for the night shift.

Compare this to Wai Lin in Tomorrow Never Dies. Even as the Brosnan era began losing its commitment to location, at least we understood she lived where we found her. She was tied to her environment—culturally, visually, narratively. It made the story feel rooted.

Then there’s the most baffling choice of all: the opening credits of NTTD. No criticism of Daniel Kleinman—he doesn’t have the full plot when designing the sequence—but invoking the flag of Japan there (even with the wrong colours) is almost insulting to fans who know the novels. Yes, Japan is where Bond “dies” in You Only Live Twice. Symbolically, the reference checks out. But NTTD has nothing to do with Japan—none of its culture, philosophy, or characters (despite Safin’s arbitrary “Eastern” aesthetics). It’s just a vague nod to an island somewhere in the Pacific. Bond’s “death journey” has none of the thematic resonance of Fleming’s Japan chapters. The film gestures toward a “sparrows’ tears” moment and gives us… Doudou.

If Bond 26 wants personality—real texture—it must commit to its locations. Pick a country that complements the villain’s arc. Fill it with meaningful allies and enemies who belong there. Let the setting shape Bond’s growth. That’s how you give a Bond film flavour again—and how you make the story feel like it had to happen there, not anywhere else.

5) Why Not the Canary Islands?

Wait—don’t run. Hear me out.

In the current cinematic landscape, cost containment isn’t optional, it’s survival. Studios are still recovering from a string of box-office flops. Audiences are fragmented across streaming platforms. And Bond 26 will almost certainly debut with a smaller budget than its predecessors—especially with a new, unproven Bond in the role. Higher risk means tighter spending. It’s no coincidence that Casino Royale filmed in Prague for budget reasons. I suspect the Bond producers are thinking the same way now: “Where can we shoot something spectacular without lighting the budget on fire?”

Enter the Canary Islands.

The Canaries are already investing aggressively in film production — sound stages, tax incentives, streamlined logistics. They’re not just competitive; they’re substantially cheaper than shooting at Pinewood or hopping across multiple countries. And they offer something most locations cannot: immense variety within a small geographic radius.

Black sand beaches. Pine forests. Snow on Teide. Tropical jungle. Lunar plateaus. Volcanic wastelands. Sand dunes. Colonial towns. Rugged cliffs. All within an hour’s flight between islands—and many within a 40-minute drive. Weather risk? Minimal. Accommodation? Plentiful. Transport? Easy. The islands can host a major production and keep it lean.

But the real question is:

Could a Bond story genuinely and organically take place in the Canary Islands?

I know I’m biased—but I’m convinced the answer is a resounding yes.

And look—I’m not naïve. The Canary Islands are not a “premium destination” in the sense that Abu Dhabi or the new Saudi mega-resorts are. You can always take the easy option: go to the Gulf, point the camera at an extravagant hotel lobby the size of Luxembourg, and voilà—instant blockbuster sheen. The Mission: Impossible franchise has been doing exactly that. It looks expensive. It looks glossy. But does it mean anything? Does it actually serve the story?

Would it make thematic sense for Bond 26?

I’d argue no.

Why drop a younger, untested Bond into the cinematic equivalent of a luxury shopping mall? Why give him a billion-dollar skyline before he’s even earned his stripes? A Bond who is still becoming Bond—still learning, still vulnerable, still rough around the edges—deserves a location that mirrors that arc. A place that seems modest at first glance, maybe even underestimated, and then reveals layers, secrets, tectonic forces moving under the surface.

The Canaries fit that perfectly.

To most of the wider audience they register as a sun-and-sand holiday spot, a modest destination compared to the spectacle of the Middle East. But that’s exactly the point. Bond begins in a place the world thinks it knows—only to discover (and reveal to us) that it is far more dangerous, strategic, and intriguing than expected. As Bond grows, the location grows with him. The viewer’s perception evolves in parallel with the hero’s.

That’s good cinema.

That’s good storytelling.

And that’s the kind of thematic symmetry the Craig era never bothered with.

A modest Bond needs a modest location—one that becomes extraordinary the deeper he wades into its mysteries. The Canary Islands can offer exactly that: not a postcard, but a crucible.

In the right hands, the islands can become what Japan was for You Only Live Twice or Istanbul was for From Russia with Love: a place that shapes the story, the villain, the allies, and Lund himself.

Sorry, I meant Bond 😉

Cheers!